|

|

|

A Bosnian Painter's Windows on War and Life

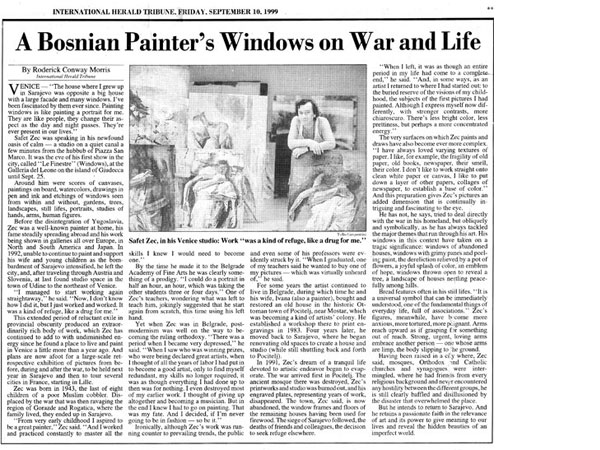

By Roderick Conway Morris Published: FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 10, 1999 www.iht.com VENICE: "The house where I grew up in Sarajevo was opposite a big house with a large facade and many windows. I've been fascinated by them ever since. Painting windows is like painting a portrait for me. They are like people, they change their aspect as the day and night passes. They're ever present in our lives." Safet Zec was speaking in his newfound oasis of calm — a studio on a quiet canal a few minutes from the hubbub of Piazza San Marco. It was the eve of his first show in the city, called "Le Finestre" (Windows), at the Galleria del Leone on the island of Giudecca until Sept. 25. Around him were scores of canvases, paintings on board, watercolors, drawings in pen and ink and etchings of windows seen from within and without, gardens, trees, landscapes, still lifes, portraits, studies of hands, arms, human figures. Before the disintegration of Yugoslavia, Zec was a well-known painter at home, his fame steadily spreading abroad and his work being shown in galleries all over Europe, in North and South America and Japan. In 1992, unable to continue to paint and support his wife and young children as the bombardment of Sarajevo intensified, he left the city, and, after traveling through Austria and Slovenia, at last found studio space in the town of Udine to the northeast of Venice. "I managed to start working again straightaway," he said. "Now, I don't know how I did it, but I just worked and worked. It was a kind of refuge, like a drug for me." This extended period of reluctant exile in provincial obscurity produced an extraordinarily rich body of work, which Zec has continued to add to with undiminished energy since he found a place to live and paint in Venice a little more than a year ago. And plans are now afoot for a large-scale retrospective exhibition of pictures from before, during and after the war, to be held next year in Sarajevo and then to tour several cities in France, starting in Lille. Zec was born in 1943, the last of eight children of a poor Muslim cobbler. Displaced by the war that was then ravaging the region of Gorazde and Rogatica, where the family lived, they ended up in Sarajevo. "From very early childhood I aspired to be a great painter," Zec said. "And I worked and practiced constantly to master all the skills I knew I would need to become one." By the time he made it to the Belgrade Academy of Fine Arts he was clearly something of a prodigy. "I could do a portrait in half an hour, an hour, which was taking the other students three or four days." One of Zec's teachers, wondering what was left to teach him, jokingly suggested that he start again from scratch, this time using his left hand. Yet when Zec was in Belgrade, post-modernism was well on the way to becoming the ruling orthodoxy. "There was a period when I became very depressed," he said. "When I saw who was winning prizes, who were being declared great artists, when I thought of all the years of labor I had put in to become a good artist, only to find myself redundant, my skills no longer required, it was as though everything I had done up to then was for nothing. I even destroyed most of my earlier work. I thought of giving up altogether and becoming a musician. But in the end I knew I had to go on painting. That was my fate. And I decided, if I'm never going to be in fashion — so be it." Ironically, although Zec's work was running counter to prevailing trends, the public and even some of his professors were evidently struck by it. "When I graduated, one of my teachers said he wanted to buy one of my pictures — which was virtually unheard of," he said. For some years the artist continued to live in Belgrade, during which time he and his wife, Ivana (also a painter), bought and restored an old house in the historic Ottoman town of Pocitelj, near Mostar, which was becoming a kind of artists' colony. He established a workshop there to print engravings in 1983. Four years later, he moved back to Sarajevo, where he began renovating old spaces to create a house and studio (while still shuttling back and forth to Pocitelj). In 1991, Zec's dream of a tranquil life devoted to artistic endeavor began to evaporate. The war arrived first in Pocitelj. The ancient mosque there was destroyed, Zec's printworks and studio was burned out, and his engraved plates, representing years of work, disappeared. The town, Zec said, is now abandoned, the window frames and floors of the remaining houses having been used for firewood. The siege of Sarajevo followed, the deaths of friends and colleagues, the decision to seek refuge elsewhere. "When I left, it was as though an entire period in my life had come to a complete end," he said. "And, in some ways, as an artist I returned to where I had started out: to the buried reserve of the visions of my childhood, the subjects of the first pictures I had painted. Although I express myself now differently, with stronger contrasts, more chiaroscuro. There's less bright color, less prettiness, but perhaps a more concentrated energy." The very surfaces on which Zec paints and draws have also become ever more complex. "I have always loved varying textures of paper. I like, for example, the fragility of old paper, old books, newspaper, their smell, their color. I don't like to work straight onto clean white paper or canvas, I like to put down a layer of other papers, collages of newspaper, to establish a base of color." And this preparation gives Zec's pictures an added dimension that is continually intriguing and fascinating to the eye. He has not, he says, tried to deal directly with the war in his homeland, but obliquely and symbolically, as he has always tackled the major themes that run through his art. His windows in this context have taken on a tragic significance: windows of abandoned houses, windows with grimy panes and peeling paint, the dereliction relieved by a pot of flowers, a joyful splash of color, an emblem of hope, windows thrown open to reveal a tree, a landscape of houses nestling peacefully among hills. Bread features often in his still lifes. "It is a universal symbol that can be immediately understood, one of the fundamental things of everyday life, full of associations." Zec's figures, meanwhile, have become more anxious, more tortured, more poignant. Arms reach upward as if grasping for something out of reach. Strong, urgent, loving arms embrace another person — one whose arms are limp, the body slipping to the ground. Having been raised in a city where, Zec said, mosques, Orthodox and Catholic churches and synagogues were intermingled, where he had friends from every religious background and never encountered any hostility between the different groups, he is still clearly baffled and disillusioned by the disaster that overwhelmed the place. But he intends to return to Sarajevo. And he retains a passionate faith in the relevance of art and its power to give meaning to our lives and reveal the hidden beauties of an imperfect world. |

|

Zec_IHT.pdf |