|

|

|

ARTS & IDEAS

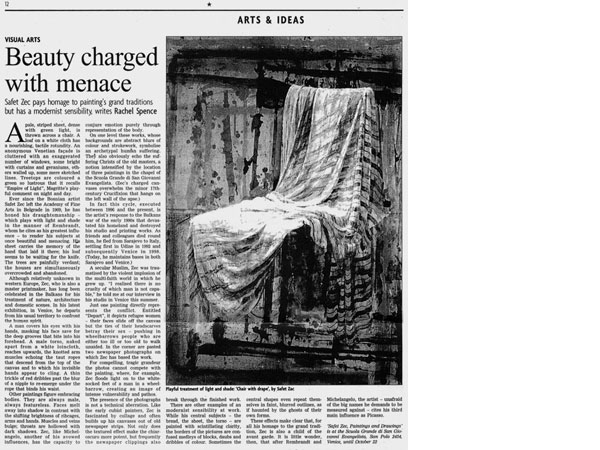

Beauty charged with menace By Rachel Spence, Financial Times Published: Sep 07, 2005 www.ft.com Apale, striped sheet, dense with green light, is thrown across a chair. A loaf on a white cloth has a nourishing, tactile rotundity. An anonymous Venetian façade is cluttered with an exaggerated number of windows, some bright with curtains and geraniums, others walled up, some mere sketched lines. Treetops are coloured a green so lustrous that it recalls "Empire of Light", Magritte's playful comment on night and day. Ever since the Bosnian artist Safet Zec left the Academy of Fine Arts in Belgrade in 1969, he has honed his draughtsmanship - which plays with light and shade in the manner of Rembrandt, whom he cites as his greatest influence - to render his subjects at once beautiful and menacing. His sheet carries the memory of the hand that laid it there; his loaf seems to be waiting for the knife. The trees are painfully verdant; the houses are simultaneously overcrowded and abandoned. Although relatively unknown in western Europe, Zec, who is also a master printmaker, has long been celebrated in the Balkans for his treatment of nature, architecture and domestic scenes. In his latest exhibition, in Venice, he departs from his usual territory to confront the human spirit. A man covers his eyes with his hands, masking his face save for the deep grooves that bite into his forehead. A male torso, naked apart from a white loincloth, reaches upwards, the knotted arm muscles echoing the taut ropes that descend from the top of the canvas and to which his invisible hands appear to cling. A thin trickle of red dribbles past the blur of a nipple to re-emerge under the rope that binds his waist. Other paintings figure embracing bodies. They are always male, always featureless. Faces melt away into shadow in contrast with the shifting brightness of ribcages, arms and hands. Muscles and veins bulge; throats are hollowed with dark shadows. Zec, like Michel-angelo, another of his avowed influences, has the capacity toconjure emotion purely through representation of the body. On one level these works, whose backgrounds are abstract blurs of colour and strokework, symbolise an archetypal human suffering. They also obviously echo the suffering Christs of the old masters, a notion intensified by the location of three paintings in the chapel of the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista. (Zec's charged canvases overwhelm the minor 17th-century Crucifixion that hangs on the left wall of the apse.) In fact this cycle, executed between 1996 and the present, is the artist's response to the Balkans war of the early 1990s that devastated his homeland and destroyed his studio and printing works. As friends and colleagues died round him, he fled from Sarajevo to Italy, settling first in Udine in 1992 and subsequently Venice in 1998. (Today, he maintains bases in both Sarajevo and Venice.) A secular Muslim, Zec was traumatised by the violent implosion of the multi-faith world in which he grew up. "I realised there is no cruelty of which man is not capable," he told me at our interview in his studio in Venice this summer. Just one painting directly represents the conflict. Entitled "Depart", it depicts refugee women - their faces slide off the canvas but the ties of their headscarves betray their sex - pushing in wheelbarrows people who are either too ill or too old to walk unaided. In the corner are pasted two newspaper photographs on which Zec has based the work. For compelling, tragic grandeur the photos cannot compete with the painting, where, for example, Zec floods light on to the white-socked feet of a man in a wheel-barrow, creating an image of intense vulnerability and pathos. The presence of the photographs is not a technical aberration. Like the early cubist painters, Zec is fascinated by collage and often builds up his canvases out of old newspaper strips. Not only does the textured effect make the chiaroscuro more potent, but frequently the newspaper clippings alsobreak through the finished work. There are other examples of an modernist sensibility at work. While his central subjects - the bread, the sheet, the torso - are painted with scintillating clarity, the borders of the pictures are confused medleys of blocks, daubs and dribbles of colour. Sometimes the central shapes even repeat themselves in faint, blurred outlines, as if haunted by the ghosts of their own forms. These effects make clear that, for all his homage to the grand tradition, Zec is also a child of the avant garde. It is little wonder, then, that after Rembrandt and Michelangelo, the artist - unafraid of the big names he demands to be measured against - cites his third main influence as Picasso. 'Safet Zec, Paintings and Drawings' is at the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista, San Polo 2454, Venice, until October 22 |

|

Zec_FT.pdf |